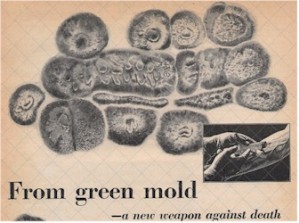

Few suspected that the quiet discovery made by Sir Alexander Fleming in a private laboratory in 1928 would snowball into being the earth-shattering breakthrough it would turn out to be. Nonetheless, snowball it did, and ended up being one of the most profound medical discoveries of the World War II era.

Fleming began experimenting with antibiotics in 1921, but it wasn’t until 1928 that he found the germ-killing properties of penicillium’s liquid secretion. At the time, however, he was unable to produce enough of this powerful penicillium secretion to actually be useful in medicine, and so his findings were swept under the rug for several years. Fleming’s work was “rediscovered” almost a decade later by a team of scientists at Oxford, and additional research from Columbia University provided strong evidence that penicillin could effectively treat infections.

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States’ demand for penicillin was so high that it could only be met by mass production- something that Fleming had deemed impossible. In that same year, pharmaceutical company Pfizer agrees to develop a method of mass production for penicillin, and devotes the next three years to researching a solution. One of the scientists on the job, Dr. Jasper Kane, suggested in 1942 that Pfizer utilize the same deep-tank fermentation methods as used in processing citric acid. The company decided to follow through with Kane’s plan and went out on a limb to invest several millions of dollars in converting a nearby plant into a plant perfected for the complex production process that would be necessary. It took only four months to get the renovated plant into functional order, and thanks to the new technology, Pfizer found itself producing over five times more penicillin than they had expected.

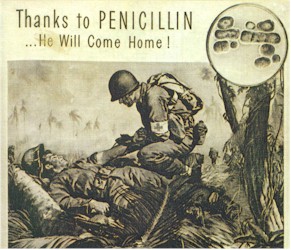

The miraculous antibiotic was first tested for the military in the spring of 1943, and it worked so well that by the fall, surgeons were using it on the battlefield to treat patients with life-endangering infections. During the span of World War II, American troops received about 85% of the nation’s penicillin production, which by 1943 totaled 231 billion units. In fact, by D-Day in 1944, almost 300 billion units of penicillin were brought ashore with Allied armed forces (270 billion of which were supplied by Pfizer, the nation’s leading producer at the time).

Penicillin quickly proved itself to be one of the safest antibacterial substances on the market, an assertion which still holds true today. It helped save countless lives, earning its nickname, the wartime “wonder drug.” Indeed, World War II was made different from any other war in history due to the remarkable infection treatment that penicillin offered to people.